This article refers to the latest released A2A protocol version (0.3.0), while noting that the specification is published as Draft v1.0.

What is A2A protocol? A common language for AI agents

Agent2Agent (A2A) Protocol is an open standard for communication between AI agents, software agents that can plan, call tools, exchange messages, and complete tasks on a user’s behalf. Like HTTP standardized communication between browsers and servers, A2A standardizes how agents talk to other agents, even when they come from different vendors, frameworks, or infrastructure.

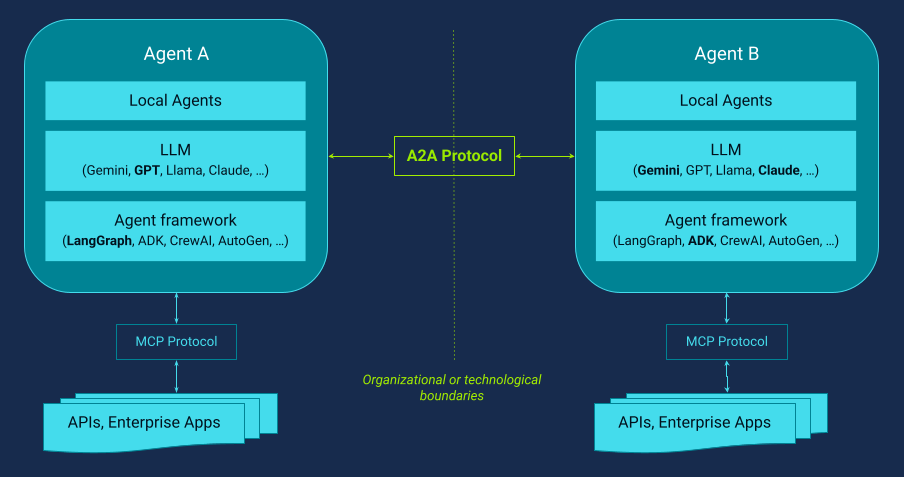

Figure 1. A2A Protocol

At a practical level, A2A defines how agents can discover each other’s capabilities and skills, send structured requests, return results, and coordinate work without needing access to one another’s internal prompts, memory, or tool stacks. A2A focuses on the interface/contract, not the internals. So, agents can collaborate while maintaining clear organizational and technological boundaries and security.

In Figure 1, we see two collaborating agents: Agent A and Agent B. Typically, one acts as the client agent (Agent A), which can discover Agent B’s capabilities and delegate a task that requires Agent B’s specific skill(s). The two agents may be built by different teams, use different models and agent frameworks, and rely on different MCP servers and tool stacks to deliver their exposed skills. Through the A2A protocol, they communicate using a unified set of standardized procedures.

Internally, each agent may also be composed of additional supporting local agents whose behavior is not directly exposed over A2A. Only the externally exposed skills of the top-level (user-facing) Agent A and Agent B are published through the A2A interface (the “A2A wrapper”), keeping internal implementation details private while still enabling dependable cross-agent collaboration.

This makes agents composable building blocks. Rather than building a single “all-in-one” agent, teams can create specialized agents (dealing with, for instance, network monitoring, firewall/policy, incident triage, or configuration/CMDB) and have them collaborate via a shared language to form auditable agent networks.

Why A2A protocol exists: Solving multi-agent integration chaos

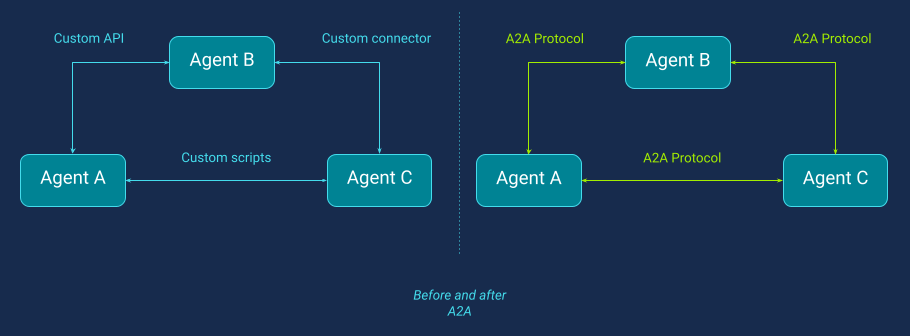

A2A was created to solve one of the earliest and most persistent multi-agent challenges: silos. Teams developed agents across different products, clouds, and frameworks. While these agents were effective in isolation, they could not reliably collaborate across environments. That meant cross-domain workflows still relied on fragile glue code, bespoke integrations, or manual handoffs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Before and after A2A Protocol

Before A2A, connecting AI agents across an enterprise looked like classic “spaghetti integration”. Every agent-to-agent workflow required its own custom API, connector, or script, and the number of fragile point-to-point links exploded as new agents were added. A2A’s goal is to provide a common interoperability layer so agents can coordinate tasks across the enterprise software estate.

Another motivation is that modern agents are often opaque (you may not know what model/tooling/internal logic they use), making direct integration risky and expensive. A2A standardizes the “agent communication contract” so organizations can safely combine specialist agents across teams and vendors.

Finally, to encourage broad, cross-vendor adoption, Google transferred A2A into an open governance model under the Linux Foundation, supporting neutrality and long-term community stewardship.

How A2A protocol works: Discovery, tasks, and agent coordination

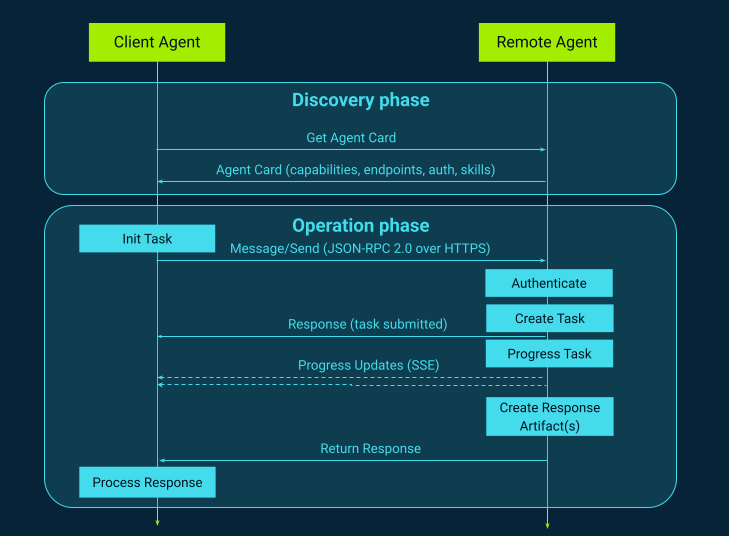

At its core, the A2A Protocol treats every AI agent as a network-accessible service that can collaborate with other agents through a shared set of interaction rules. Rather than forcing all agents into a single platform or framework, A2A assumes that agents will remain distributed, running in different environments, written in different languages, and managed by different teams or vendors. The architecture, therefore, focuses on standardizing the interaction layer, not the internal reasoning. In practical terms, A2A defines how a “client agent” can connect to a “remote agent,” send it a task, receive progress updates, and obtain a final result, even if the remote agent is a black box (Figure 3). This separation is a central design choice: A2A does not try to standardize prompts, memory, or toolchains, but only inter-agent communication.

Figure 3. A2A Protocol Flow

A2A commonly uses familiar web building blocks like HTTP(S) endpoints and JSON-RPC-style request/response messaging. They facilitate deployment across enterprise infrastructure and integration with existing gateways, auth layers, and observability. Many A2A implementations also support streaming updates (for example, using Server-Sent Events - SSE) so that a long-running agent task can report intermediate progress rather than behaving like a “single blocking API call.” That matters because agent work is often asynchronous: an agent may need to query systems, wait on external checks, run multi-step plans, or coordinate with other agents before it can produce a final output.

The most important architectural element that enables interoperability is the Agent Card. Each A2A-compliant agent publishes a small metadata document (typically JSON) that describes what the agent is, what it can do, how to talk to it, and what authentication it requires. Think of it like a mix of a “service discovery record” and a “capabilities description.” A client agent can fetch the agent card (often from a well-known path like https://

A2A protocol core components: Agent cards, skills, and task lifecycle

A2A protocol actors: User, client agents, and remote agents explained

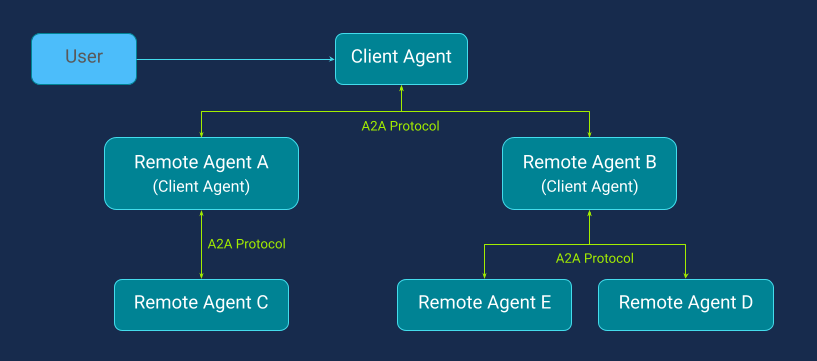

A2A documentation typically describes three roles: a User, an A2A Client (Client Agent), and an A2A Server (Remote Agent) (Figure 4). The user interacts with the client agent. The client agent delegates tasks to remote agents (Agent A or/end Agent B). Remote agents can also play the role of Client Agents, delegating subtasks to the next level of remote agents (Agents C, D, E). Importantly, the remote agents are treated as independent, as they have their own identity, capabilities, and policies.

Figure 4. Actors in A2A Protocol

In Figure 4, the A2A agents are shown for simplicity in a tree-like structure, but in practice, an A2A agent network can take any topology (including a mesh) as long as it fits the workflow and collaboration needs.

Agent card: How A2A enables discovery and capability advertising

Discovery is the step that enables delegation. Before a client agent can ask for help, it must know what agents exist and what they can do. The agent card provides that contract: identity, capabilities, endpoints, skills, and security requirements. In enterprise environments, agent cards can be fetched directly from a host or via a registry, but the protocol-level idea is the same: the agent card is the “menu” that tells other agents what’s available.

{

"protocolVersions": ["0.3.0"],

"name": "NetOps Codilime Agent",

"description": "Network troubleshooting agent.",

"supportedInterfaces": [

{"url": "https://netops.agents.codilime.com/a2a/v1", "protocolBinding": "JSONRPC"},

{"url": "https://netops.agents.codilime.com/a2a/grpc", "protocolBinding": "GRPC"},

],

"provider": {

"organization": "Codilime",

"url": "https://codilime.com"

},

"iconUrl": "https://netops.agents.codilime.com/icon.png",

"version": "1.2.0",

"documentationUrl": "https://netops.agents.codilime.com/api",

"defaultInputModes": ["text/plain", "application/json"],

"defaultOutputModes": ["text/plain", "application/json"],

-- parts are demonstrated and explained in the next sections --

"capabilities": {}

"skills": []

"securitySchemes": {}

"security": []

}

Figure 5. Example agent card json

In the example Agent Card (Figure 5), several fields define the agent’s identity, compatibility, and connection details. The protocolVersions field tells clients which A2A spec versions the agent supports (here: 0.3.0), while supportedInterfaces advertises the concrete endpoints and protocol bindings that clients can use to connect, commonly JSON-RPC over HTTP and optionally gRPC for higher-performance deployments. The provider, iconUrl, version, and documentationUrl fields make the agent easier to trust and adopt in enterprise settings by clearly identifying who owns it, where to find official docs, and which implementation build is currently running. Finally, defaultInputModes and defaultOutputModes define the agent’s default content formats (e.g., plain text and JSON), so client agents know how to structure requests and interpret responses without guesswork. However, these defaults can be overridden at the individual skill level using inputModes and outputModes in the skill definition (as shown below). Defining agent capabilities and skills in A2A protocol In an Agent Card (Figure 6), the capabilities block describes what protocol-level features the agent supports. For example, streaming: true means the agent can send incremental updates (useful for long-running tasks), while pushNotifications: true indicates it can proactively notify clients rather than relying only on polling. Flags like stateTransitionHistory and extendedAgentCard further signal whether the agent exposes richer execution history or an authenticated “extended” version of its card, helping client agents understand what interaction patterns are possible up front.

{

...

"capabilities": {

"streaming": true,

"pushNotifications": true,

"stateTransitionHistory": false,

"extendedAgentCard": false

},

"skills": [

{

"id": "detect-network-incident",

"name": "Detect network incidents",

"description": "Detect anomalies such as packet loss or latency spikes",

"tags": ["network", "observability", "incident"],

"inputModes": ["application/json", "text/plain"],

"outputModes": ["application/json"],

"examples": [

"Detect anomalies in the last 30 minutes",

"Identify packet loss incidents in region eu-central"

],

},

{

"id": "triage-incident",

"name": "Triage incident",

"description": "Identify likely root cause and impacted services/sites",

"tags": ["network", "triage"],

"inputModes": ["application/json", "text/plain"],

"outputModes": ["application/json", "text/plain"],

"examples": [

"Triage incident INC-123",

"Which services are impacted by packet loss on edge-router-7?"

],

},

...

]

...

}

Figure 6. Example agent card - capabilities and skills

The skills section is where the agent advertises what it can do, expressed as discrete capabilities like detecting network incidents or triaging an incident. Each skill includes an ID, a human-readable description, tags for user request routing, and the supported inputModes/outputModes (e.g., JSON for automation, text for conversational use), plus short examples that show how to call the skill in practice. Together, capabilities and skills turn the AgentCard into a discoverable contract: other agents can quickly determine whether this agent fits a workflow and how to structure requests for it.

A2A security: OAuth2, API keys, and enterprise authentication

A2A treats security as a discoverable contract: each agent publishes its supported authentication methods in the AgentCard under securitySchemes, and then declares the required permissions in security (for example, OAuth2 scopes) (Figure 7). Importantly, A2A doesn’t implement identity itself, it advertises requirements, while the enterprise identity provider (OIDC/OAuth2) and gateways enforce authentication and authorization. The standard defines multiple securitySchemes types, including API keys, HTTP auth (e.g., Basic or Bearer), OAuth2, OpenID Connect discovery, and mutual TLS (mTLS). These schemes facilitate agents to integrate cleanly with existing enterprise security models.

Agent Card (continued)

{

...

"securitySchemes": {

"OAuth2": {

"type": "oauth2",

"description": "OAuth2 access token required (Bearer).",

"flows": {

"clientCredentials": {

"tokenUrl": "https://idp.codilime.com/oauth2/token",

"scopes": {

"netops.read": "Read-only operations (telemetry, inventory, triage).",

"netops.change": "Change operations (policy/remediation actions)."

}

}

}

}

},

"security": [

{ "OAuth2": ["netops.read"] }

],

...

}

Figure 7. Example agent card - security schemes

OAuth2 scopes in A2A (presented in the example) should be understood as permissions carried by the caller’s access token (e.g., netops.read, netops.change). The Agent Card can advertise supported OAuth flows and available scopes via securitySchemes, and it can declare required scopes via the security field. Thus, a client knows what authorization is needed before calling the agent. However, the A2A standard does not currently define a machine-readable way to map scopes to individual skills (it is not derived from skill tags either). This mapping is typically enforced by the agent or gateway as a provider-specific policy and optionally documented per skill.

If the remote agent requires user-based authorization (OAuth2/OIDC on behalf of the user), then the first time the user uses it, the app typically needs to redirect the user to the Identity Provider (IdP) login/consent screen. After the user signs in and grants consent, your app receives tokens and can call the remote A2A agent with Authorization: Bearer

A2A task lifecycle: From submission to completion

A2A task execution typically starts when a client sends a message/send request containing one or more message “parts” (Figure 8).

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"id": "req-001",

"method": "message/send",

"params": {

"message": {

"role": "user",

"messageId": "msg-001",

"contextId": "ctx-incident-123",

"parts": [

{ "kind": "text",

"text": "Triage incident INC-123 and suggest next actions."

},

{ "kind": "data",

"data": {

"skillId": "triage-incident",

"incidentId": "INC-123",

"modelPreference": "gpt-4o-mini",

"dryRun": true

}

}

]

}

}

}

Figure 8. Init a task by message/send

This message/send request uses a standard JSON-RPC 2.0 envelope (jsonrpc, id, method) to submit a user message to an A2A agent. The message combines multiple parts: a TextPart with the human instruction and a DataPart carrying structured parameters such as the target incidentId, a skill hint (skillId: triage-incident), and lightweight runtime preferences (modelPreference, dryRun). In multimodal scenarios, the parts array can also include other kinds of content, most commonly FilePart (e.g., logs, configs, topology diagrams, screenshots), allowing agents to exchange text, structured data, and files in a single task request.

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"id": "req-001",

"result": {

"kind": "task",

"id": "task-8c2f3b21",

"contextId": "ctx-incident-123",

"status": {

"state": "submitted",

"message": {

"kind": "message",

"role": "agent",

"messageId": "status-task-8c2f3b21-1",

"taskId": "task-8c2f3b21",

"contextId": "ctx-incident-123",

"parts": [

{ "kind": "text",

"text": "Task submitted. Starting incident triage for INC-123."

}

]

}

}

}

}

Figure 9. Example response: task created / submitted

This response acknowledges the message/send call by returning a JSON-RPC result that creates a new Task (kind: "task") with a unique ID and links it to the ongoing conversation via contextId. The status state is set to submitted, meaning the agent has accepted the request and queued it for processing, and the embedded status message provides an immediate human-readable confirmation (“Starting incident triage for INC-123”). The returned taskId is the handle the client uses to track progress (poll with tasks/get or stream updates) until the task reaches a terminal state like completed or failed.

A task created via message/send does not always proceed directly to completion: the remote agent may reject the request (e.g., unsupported operation or insufficient permissions), or suspend execution by transitioning the task into an input-required state when additional data is needed (such as a change ticket ID, confirmation, or extra logs) before it can continue. A2A also supports user control over long-running work. Clients can explicitly cancel an in-progress task (e.g., via tasks/cancel), moving it into the canceled state rather than letting it run indefinitely. In addition, some A2A implementations include a tasks/list capability so clients can enumerate active and historical tasks and quickly check their current lifecycle status without tracking every task ID manually.

Multi-turn collaboration: Streaming task updates with Server-Sent Events (SSE)

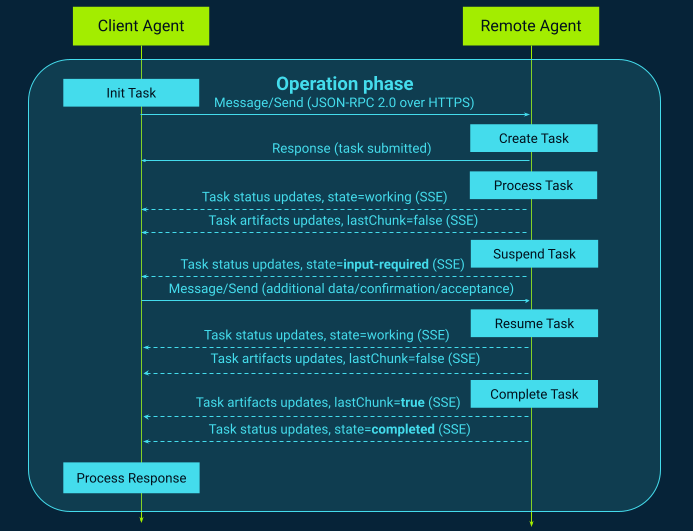

Figure 10 shows a typical multi-turn interaction between an A2A Client Agent and a Remote (Server) Agent. The client starts by sending a message/send request to initiate work. The remote agent acknowledges the request by creating a Task and returning a unique taskId (with an initial state such as submitted). From that point, the task progresses through a lifecycle (e.g., submitted → working → completed/failed), and the client can either poll the task status using tasks/get or receive real-time streaming updates via SSE (commonly through tasks/sendSubscribe / streaming endpoints).

Figure 10. Example response: task created / submitted

For streaming collaboration, the A2A standard distinguishes between progress and outputs using two event types: TaskStatusUpdateEvent and TaskArtifactUpdateEvent. TaskStatusUpdateEvent communicates the current task state (working, input-required, etc.) and can include additional details such as step-level messages (“Pulling telemetry…”, “Correlating devices…”) that are highly valuable for GUI feedback during long-running tasks. TaskArtifactUpdateEvent is used to deliver artifacts, i.e., intermediate and final results produced by the task. When artifacts are streamed in chunks, the protocol uses fields such as append and lastChunk to indicate whether an artifact is still being produced or has been fully completed.

During execution, the agent may not always be able to continue autonomously. If the workflow requires clarification, missing input, or user approval (e.g., a change ticket ID or confirmation to proceed), the agent transitions the task into input-required and emits a TaskStatusUpdateEvent explaining what is needed. While waiting, the task is effectively suspended, and it resumes only after the client sends another message providing the missing data (a new turn in the same task).

A2A does not define a separate “final result” message. The task completion is signaled by sending the final TaskArtifactUpdateEvent updates with lastChunk=true for completed artifacts, and issuing a final TaskStatusUpdateEvent with state=completed. This event-driven model makes long-running, multi-step workflows transparent, interactive, and auditable, instead of being “silent” fire-and-forget automation.

A2A artifacts: Returning structured data, files, and multi-part results

Artifacts are a first-class concept in A2A. Instead of treating every result as plain text, agents can return one or more Artifacts composed of typed parts. Each part can be a TextPart (human-readable explanation), a DataPart (structured JSON payload such as a policy diff, impacted device list, or risk summary), or a FilePart (binary content like generated configs, PDFs, diagrams, or log bundles, either inlined or referenced by URI). This design encourages agents to produce outputs that are both user-friendly and machine-consumable, enabling downstream agents to reliably parse and act on results.

{

"name": "triage-and-remediation-output",

"description":

"Incident triage summary, structured findings, and generated deliverables.",

"parts": [

{

"kind": "text",

"text":

"Root cause likely on edge-router-7 (uplink Gi0/2). Recommended action: fail over to backup uplink and monitor packet loss for 30 minutes."

},

{

"kind": "data",

"data": {

"incidentId": "INC-123",

"rootCause": {

"summary": "Interface errors on edge-router-7 uplink Gi0/2",

"confidence": 0.81

},

"impactedServices": [

"payments-api",

"customer-portal"

],

"recommendedActions": [

{

"action": "failover-uplink",

"device": "edge-router-7",

"fromInterface": "Gi0/2",

"toInterface": "Gi0/3"

},

{

"action": "monitor",

"metric": "packet_loss",

"durationMinutes": 30

}

]

}

},

{

"kind": "file",

"file": {

"name": "change-request-draft.pdf",

"mimeType": "application/pdf",

"uri":

"https://netops.agents.codilime.com/artifacts/task-8c2f3b21/change-request-draft.pdf"

}

}

],

"index": 0,

"append": false,

"lastChunk": true

}

Figure 11. Example multi-part artifact

This example in Figure 11 illustrates how A2A outputs are not limited to plain text: a single Artifact can bundle multiple content types in a predictable structure. A TextPart gives a concise human summary, a DataPart provides machine-readable results (incident ID, root cause, impacted services, recommended actions), and FileParts deliver larger deliverables such as a change request document. Thanks to chunking semantics like append and lastChunk, the same artifact format can support both streaming intermediate outputs and delivering final results in a clean, consumable way.

Official A2A SDKs: Python, Go, JavaScript, Java, and .NET support

The A2A project doesn’t just publish a protocol spec. It also provides official multi-language SDKs (currently including Python, Go, JavaScript, Java, and .NET) to make adoption straightforward in real systems. These SDKs typically include ready-made server and client implementations, strongly-typed models for AgentCards, skills, tasks, messages/parts, and artifacts, plus helpers for capability discovery, task lifecycle management, and structured task updates. In practice, they help teams move from “reading a spec and implementing it manually” to dropping in a compliant A2A server wrapper around an existing agent (or consuming a remote agent via a client), while benefiting from production-friendly integrations such as HTTP frameworks (e.g., FastAPI/Starlette), optional gRPC transport support, and OpenTelemetry tracing in some SDKs.

A2A in practice: Common gaps and workarounds

A2A provides a solid baseline for agent-to-agent interoperability, but practical deployments quickly expose gaps that matter for automation at scale. The limitations below are the most common friction points reported by implementers, especially when aiming for deterministic orchestration and strong governance.

Lack of skill parameterization (input/output schemas) in the core standard

A2A standardizes how agents communicate, but it does not yet require a machine-readable definition of skill inputs and outputs (e.g., JSON Schema or typed fields). Agent Cards can list skills with name, description, inputModes/outputModes, and examples—but that still leaves ambiguity around required parameters, types, and validation rules. This makes fully automated orchestration harder: LLM planners can discover “what skills exist,” but they often cannot reliably determine “what exact structured data must be provided” without external documentation. This gap is widely recognized by the community, with open feature proposals calling for optional structured field definitions to make skill I/O deterministic and toolable.

Lack of a native mechanism to directly request a specific skill

In practice, A2A interactions often begin with message/send, where a client sends a natural-language message plus optional structured parts—and the server-side agent decides what to do. This design keeps the protocol flexible, but it weakens determinism: there is no universally enforced, first-class “invoke skill X” semantics in the core workflow. As a result, skill invocation can become implicit, depending on how the server interprets the message, which is not ideal for structured automation, testing, or strict workflow control. Many implementations solve this informally (e.g., embedding a skillId field inside the DataPart), but because this is not standardized, cross-vendor consistency and portability remain challenging. This also increases the risk of authorization creep described below.

Authorization happens too late and too indirectly (authorization creep risk)

A2A supports authentication schemes, but it does not prescribe a standard authorization model—meaning that once a client agent is authenticated, it is typically up to the remote agent to decide whether the user is allowed to perform the requested actions. In multi-agent systems, this creates a serious risk: the agent may only determine which internal skills/tools it needs after it has already accepted the task, leading to late or implicit authorization checks (or inconsistent enforcement across tools). Security analysis in the ecosystem explicitly warns about “authorization creep,” where agents accumulate power to act across systems without robust, explicit delegated user authorization tied to specific actions/skills. Community discussions and issues propose “delegated authorization” patterns to ensure user permissions are validated before any sensitive tool/skill execution occurs.

A2A vs MCP: When to use Agent-to-Agent vs Model Context Protocol

A detailed, hands-on comparison of A2A and MCP (Model Context Protocol), with real implementation patterns, deployment tradeoffs, and security pitfalls, deserves a separate blog post. Here, I’ll keep it practical but high-level: what problems they solve, where they overlap, and where they fundamentally differ. You can read more about the MCP protocol here.

At a glance, A2A and MCP can look like they compete, but they operate at different layers of the stack. A2A standardizes how agents communicate with other agents (horizontal: agent ↔ agent): discovery (Agent Cards), task delegation, progress updates, and artifacts. MCP standardizes how an agent or AI app connects to tools, data sources, and contextual resources (vertical: agent/app ↔ tools/resources/prompts). A helpful mental model is: A2A is coordination between autonomous actors, while MCP is capability/context injection into a single actor. A2A has been explicitly framed as complementary to MCP rather than a replacement.

They still share important common ground. Both protocols exist because the ecosystem was becoming a patchwork of bespoke integrations: every tool needed custom glue code, and every framework exposed capabilities differently. Both promote standardized discovery and invocation, and both assume enterprise realities: governance, auditability, policy enforcement, and controlled rollout of capabilities as agent autonomy increases.

The clearest divergence is what each protocol treats as the “unit” of interoperability. In A2A, the primitive is a Task. A client agent submits work to a remote agent and receives progress as the task moves through states. A2A commonly exposes endpoints such as tasks/get and streaming via tasks/sendSubscribe (SSE) for longer-running work. In MCP, the primitives are Tools, Resources, and Prompts exposed by an MCP server, letting the model/app invoke concrete operations in a standardized way, hence the “USB-C for AI apps” analogy.

In real systems, a common shortcut is the “agents as tools” pattern. Instead of doing true peer-to-peer agent collaboration via A2A, teams often treat specialist agents as callable endpoints inside one orchestrator (similar to tool invocation). This reduces distributed complexity and makes guardrails easier (“one brain”), but it can also undermine the core promise of A2A: autonomy, clean delegation, standardized progress reporting, and task lifecycle management across independently deployed services. And once you combine the two A2A agents that internally use MCP tools, authorization becomes harder. You must align A2A skill permissions with MCP tool/resource permissions, and discovery must never be mistaken for permission. That’s why mature deployments trend toward delegated tokens, policy decision points, and audit trails that connect “A2A task requested” with “MCP tool executed.”

It’s tempting to think that A2A becomes unnecessary once MCP is in place, especially because MCP adoption has been faster and the tooling ecosystem has rallied around it as the default integration layer. MCP delivers immediate value: it connects models to systems, and most teams feel that “tool access” is the first real bottleneck. This has fueled a narrative that A2A is less relevant or even redundant. Some commentators explicitly argue that A2A adds complexity on top of MCP without enough short-term payoff, which partly explains why MCP feels more visible in day-to-day engineering discussions. However, a more careful interpretation is that MCP and A2A are complementary. MCP standardizes execution primitives, while A2A standardizes delegation between autonomous services. In other words, MCP helps you build a powerful agent, and A2A helps you build a system of agents. As architectures mature from “one orchestrator agent + tools” into distributed, team-owned, independently deployed agent services, A2A becomes more important, not less, because it provides the missing coordination contract (discovery, task lifecycle, progress streaming, and trust between agents).

A2A protocol summary: Building enterprise multi-agent systems with standardized interoperability

A2A (Agent2Agent) v0.3.0 is best understood as an interoperability contract for building systems of agents. It standardizes agent discovery, secure task delegation, progress streaming, and structured outputs so independently built agents can collaborate across vendors and enterprise environments. The biggest practical benefit is eliminating “spaghetti integrations” by giving organizations a reusable, auditable way to compose specialist agents into cross-domain workflows, without forcing a single framework, model, or toolchain.

At the same time, A2A is still early-stage and some missing pieces matter for production-grade orchestration: there’s no core machine-readable skill I/O schema, no fully standardized “invoke skill X” primitive, and authorization can become indirect (“authorization creep”) if not designed carefully. The encouraging part is that A2A is being developed under open governance (Linux Foundation) and the community is actively discussing real-world requirements—such as adding optional structured input/output field definitions for skills—so we should expect the protocol to mature rapidly as agentic frameworks, LLM capabilities, and broader GenAI/agentic architectures evolve.