What is Model Context Protocol (MCP)?

MCP (Model Context Protocol) is an open and evolving JSON-RPC-based standard that lets any AI application discover tools, reusable prompts, resources, and other context from remote MCP servers, then invoke them through a stateful session rather than ad-hoc REST API calls.

MCP also standardizes the protocols and rules by which an MCP server interacts with AI applications through an MCP client, enabling secure and consistent access to resources and user data from the application, data that can then be processed or acted upon by an MCP server. First, it was published by Anthropic in November 2024 and is now maintained by an open-source spec on GitHub. This blog refers to the MCP 2025-11-25 version.

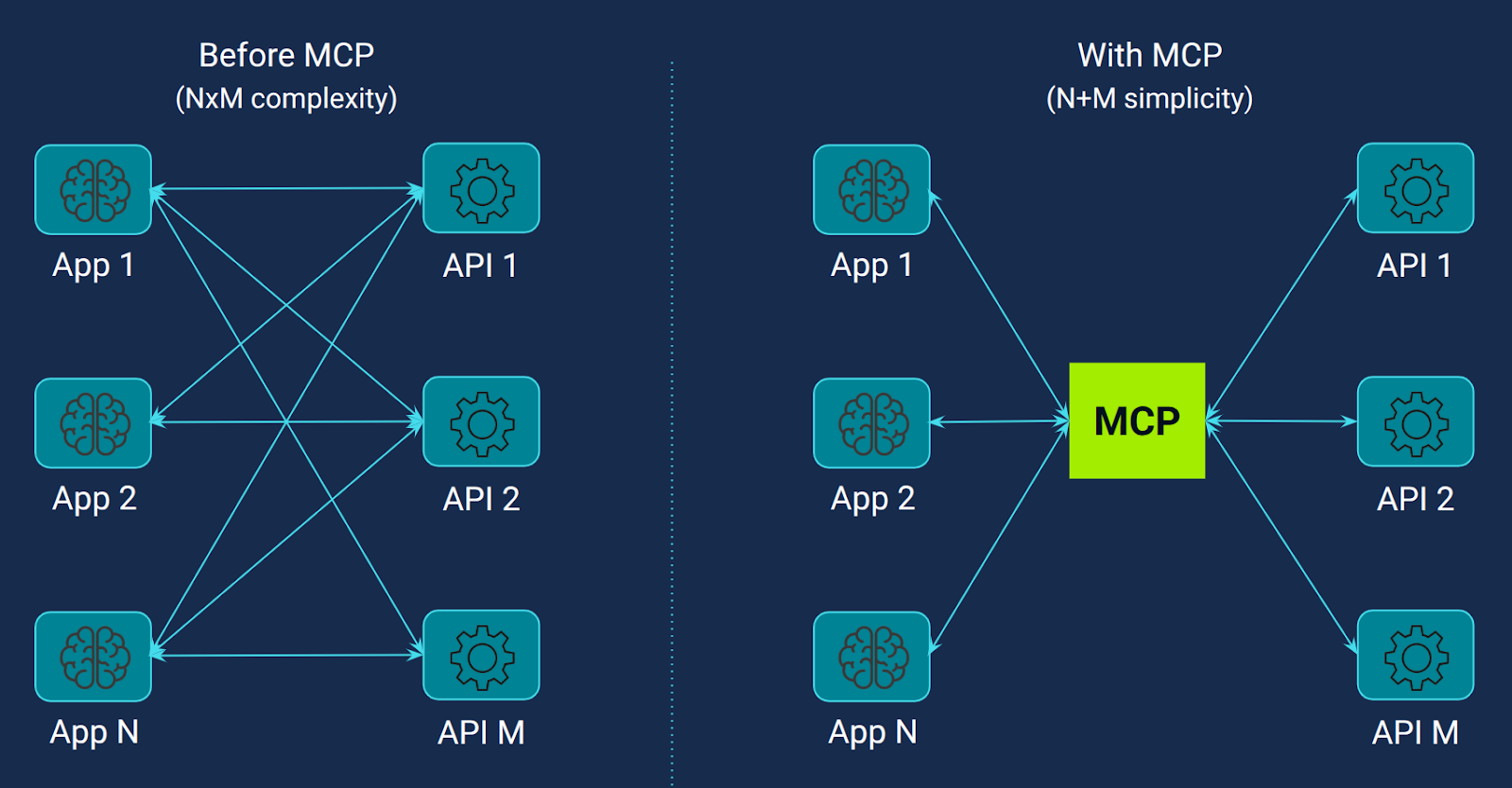

Why MCP was created: Solving the N×M integration problem

One of the significant challenges in AI development is the issue termed the "N × M integration problem", as identified by Anthropic. This problem arises when integrating N tools (such as Slack, GitHub, or databases) with M model front-ends (like ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude). Without a standardized approach, each combination of model and tool requires a unique adapter, leading to a proliferation of custom integrations, resulting in N × M bespoke solutions. Consequently, developers are burdened with maintaining numerous intricate glue-code modules.

MCP addresses this challenge by providing a standardized framework for tool integration. If each tool vendor exposes its functionalities through an MCP server, any MCP-aware model front-end can seamlessly interact with these tools without the need for additional custom code. This approach transforms the N × M problem into a more manageable N + M scenario, significantly reducing the complexity and maintenance overhead associated with AI integrations (Figure 1).

Unifying tool descriptions under MCP gives LLM vendors a single, standardized format for defining tools (including JSON‑RPC schemas, descriptions, and parameters), which enables consistent training or fine‑tuning of models to accurately detect when a tool is needed and how to parameterize it. Before MCP, each vendor had its own format, leading to fragmentation, inconsistent tool invocation, and training data mismatches. With MCP, models can dynamically discover available tools via manifests, operate across multiple backends, and make more reliable tool-calling decisions, significantly improving accuracy and reducing prompt complexity.

Also, software and platform vendors are increasingly looking to expose their core functionalities through standardized MCP servers, aiming to encourage AI application developers to securely integrate with their products in much the same way they already do with traditional APIs (Figure 1).

By adopting MCP, these vendors can more effectively promote their offerings as part of a broader AI ecosystem, where roles and responsibilities are well defined, and trust boundaries are clear. At the same time, AI application and agent developers benefit from the use of standardized tools, streamlining integration and allowing them to focus on innovation rather than custom connectors or security workarounds.

So, a wide range of stakeholders stand to benefit from the adoption of an MCP standard. MCP is often likened to the USB-C standard for AI, offering a universal interface that simplifies connections between AI models and various tools, much like USB-C standardizes inter-device connections.

How MCP works: Architecture and implementation

MCP architecture overview: Client-server model

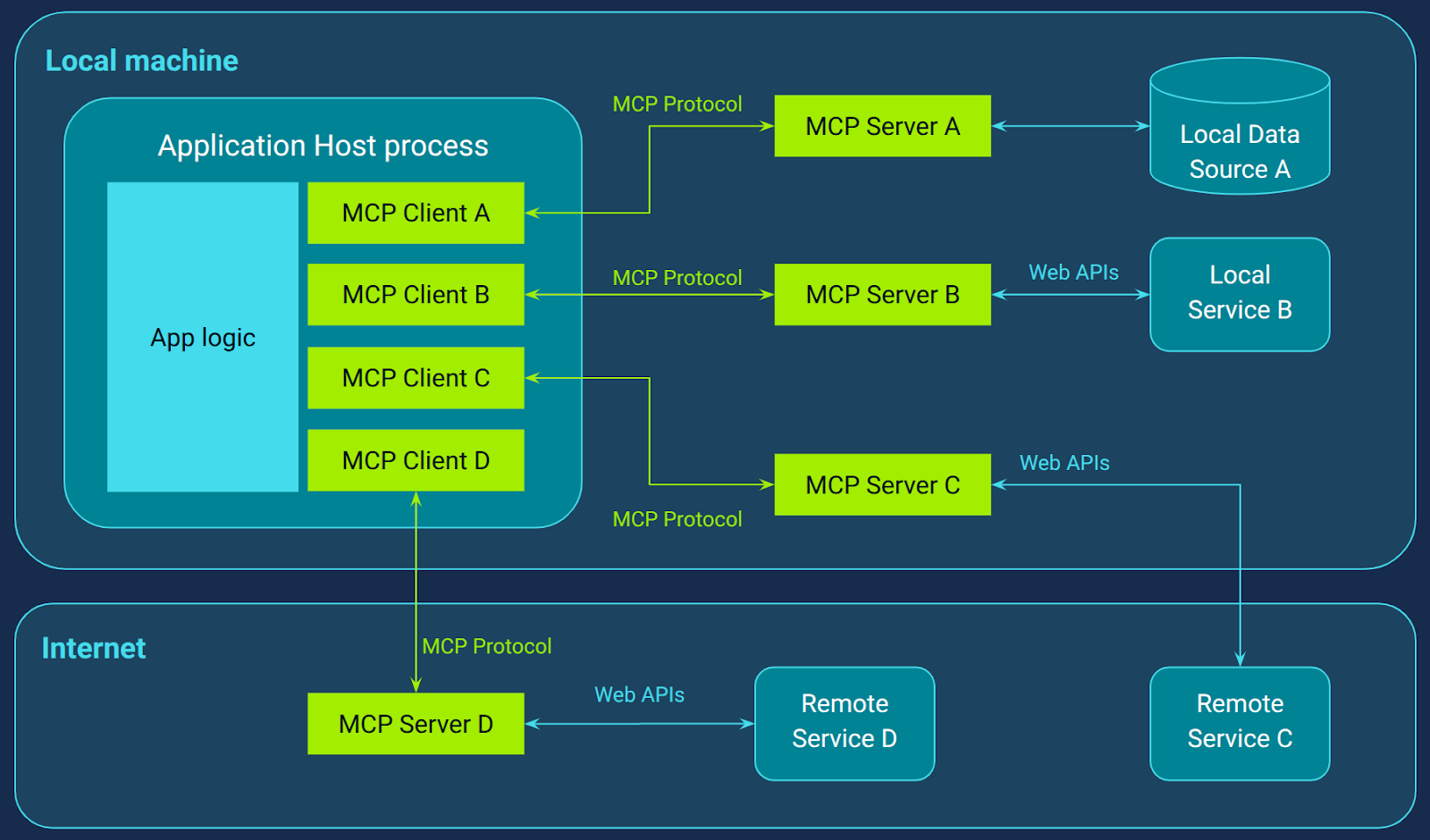

MCP is built on a robust client–server architecture (Figure 2), with multiple clients running per host and connected to distinct servers. At its core, a host application (like an LLM-powered agent) can spin up several isolated MCP client sessions, each maintaining a stateful JSON-RPC channel with its own MCP server.

All communication travels via JSON‑RPC, transformed into a stateful session protocol, meaning clients and servers can continually interact within an established session. MCP’s architecture lets hosts coordinate multiple client-driven workflows with external tools, all over a reliable, stateful JSON-RPC protocol, ensuring security, modularity, and advanced tool orchestration.

This design achieves two powerful goals: secure isolation and persistent context. Each client-server pair has its own session, enforcing clear boundaries so that protocols, permissions, and policies don’t bleed across domains. Agents can call a tool, get results, and continue reasoning in the same session, enabling multi-step logic and complex workflows with context retained server-side if necessary.

Application host process: Orchestrating MCP clients

The application host process in MCP acts as a central container and orchestrator, managing the lifecycle of multiple client instances and ensuring secure and organized operation. It creates and controls connections to MCP servers, enforcing permissions and security policies so that each client operates within well-defined boundaries.

The host also handles user authorization and consent, deciding which clients can invoke which tools, and bridges the AI/LLM’s reasoning and sampling routines by coordinating context exchange across clients and their sessions. By aggregating context from various server interactions, the host enables the LLM to maintain coherent, multi-step workflows without leaking data or permissions between clients. In short, the host is the gatekeeper and coordinator; applications like AI agents, Claude Desktop, and IDEs rely on it to safely and efficiently integrate with external tools via MCP.

MCP clients: Managing server connections

An MCP client maintains a dedicated, one-to-one connection with its corresponding server. Each client is instantiated by the host process and establishes a stateful session that begins with protocol and capability negotiation to ensure both sides understand the features supported. Throughout the session, the client acts as a message router, seamlessly forwarding JSON‑RPC requests and responses, managing subscriptions and notifications, and handling disconnections or timeouts gracefully. Because each client only communicates with a single server, it maintains strong security boundaries, preventing context or permission leaks across different services.

MCP servers: Exposing tools, resources, and prompts

An MCP server operates as a lightweight, focused process that exposes specialized context and capabilities via standardized protocol primitives, such as tools, resources, and prompts, to any connected client. Each server encapsulates a domain-specific responsibility, such as interacting with a file system, a database, or network APIs, and operates independently, ensuring modularity and maintainability.

Through its MCP interface, the server declares executable tools (e.g., commands or API actions), resources for contextual data access, and optionally, reusable prompt templates. Servers enforce security constraints, ensuring clients only access authorized resources or operations. They can run as local processes (e.g., via standard I/O) or as remote services (e.g., HTTP with SSE), making them versatile and easy to integrate in distributed environments (see Transport section).

Connecting local and remote data sources and services with MCP

Local data sources in the MCP ecosystem refer to files, databases, and services that reside directly on the user's computer. MCP servers adapt these resources into standardized MCP primitives, such as tools, prompts, or context objects, making them available to LLM-powered applications through secure, stateful sessions.

On the other hand, remote services encompass any external APIs or systems accessible over the internet, like cloud databases, REST APIs, or enterprise applications. MCP servers can bridge these networked services by wrapping them into the same consistent protocol, allowing LLM agents to seamlessly invoke or query them during workflows. By treating both local and remote endpoints as equal peers within MCP, developers gain a unified, secure, and context-aware interface for prompting, orchestrating, and reasoning over a wide variety of data sources and services.

MCP session lifecycle: Initialization to shutdown

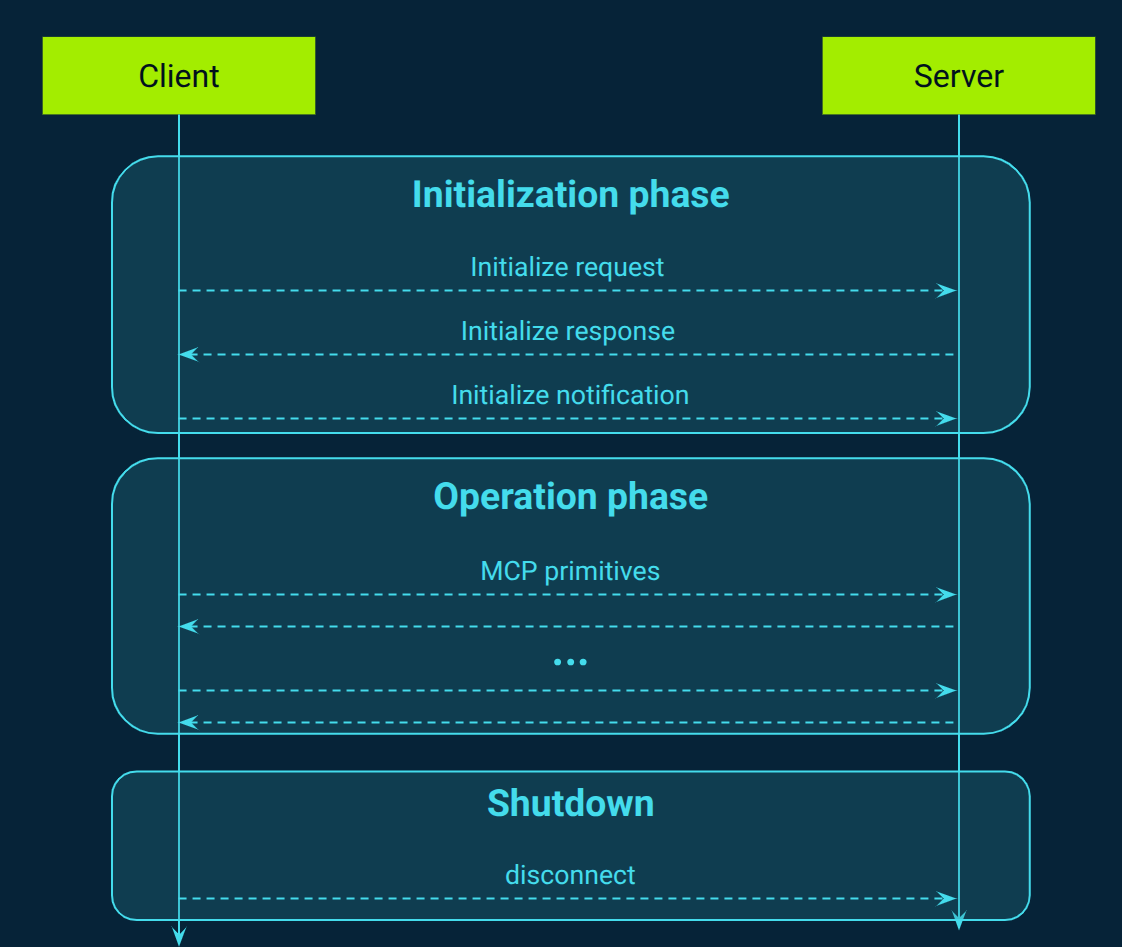

MCP defines a rigorous three-phase lifecycle that governs client–server interactions, ensuring robust session establishment, operation, and clean termination (Figure 3).

In the Initialization phase, the client always begins by sending an initialization request, containing its supported protocol version, declared capabilities (sampling, elicitation, or roots), and metadata about the client implementation. The server then responds with a matching or compatible protocol version and its own set of capabilities (prompts, tools, resources) along with server metadata. Once the server has responded successfully, the client sends a notification to confirm readiness, capabilities are negotiated by both sides, and only after that point can meaningful operations begin.

During the operation phase, both client and server exchange requests, notifications, and responses in accordance with the negotiated protocol version and declared capabilities. This phase supports bidirectional message flow and flexible interaction sequences. For example, the client may call tools/list to discover server tools, while the server may initiate sampling or elicitation requests if those capabilities were negotiated. Parties must refrain from invoking any features that were not agreed upon in the initialization handshake, ensuring safe and predictable communication throughout the session.

Finally, the Shutdown phase marks the graceful termination of the MCP session. No specific protocol messages are required. The client or occasionally the server simply closes the underlying transport connection. Throughout the session lifecycle, implementations are encouraged to enforce timeouts on requests and robust error handling that covers version mismatches, capability negotiation failures, and unexpected disconnects.

MCP server features: Tools, resources, and prompts

MCP defines essential interaction primitives that servers expose to clients, facilitating standardized communication between AI models and external data sources or tools. They are shortly described below.

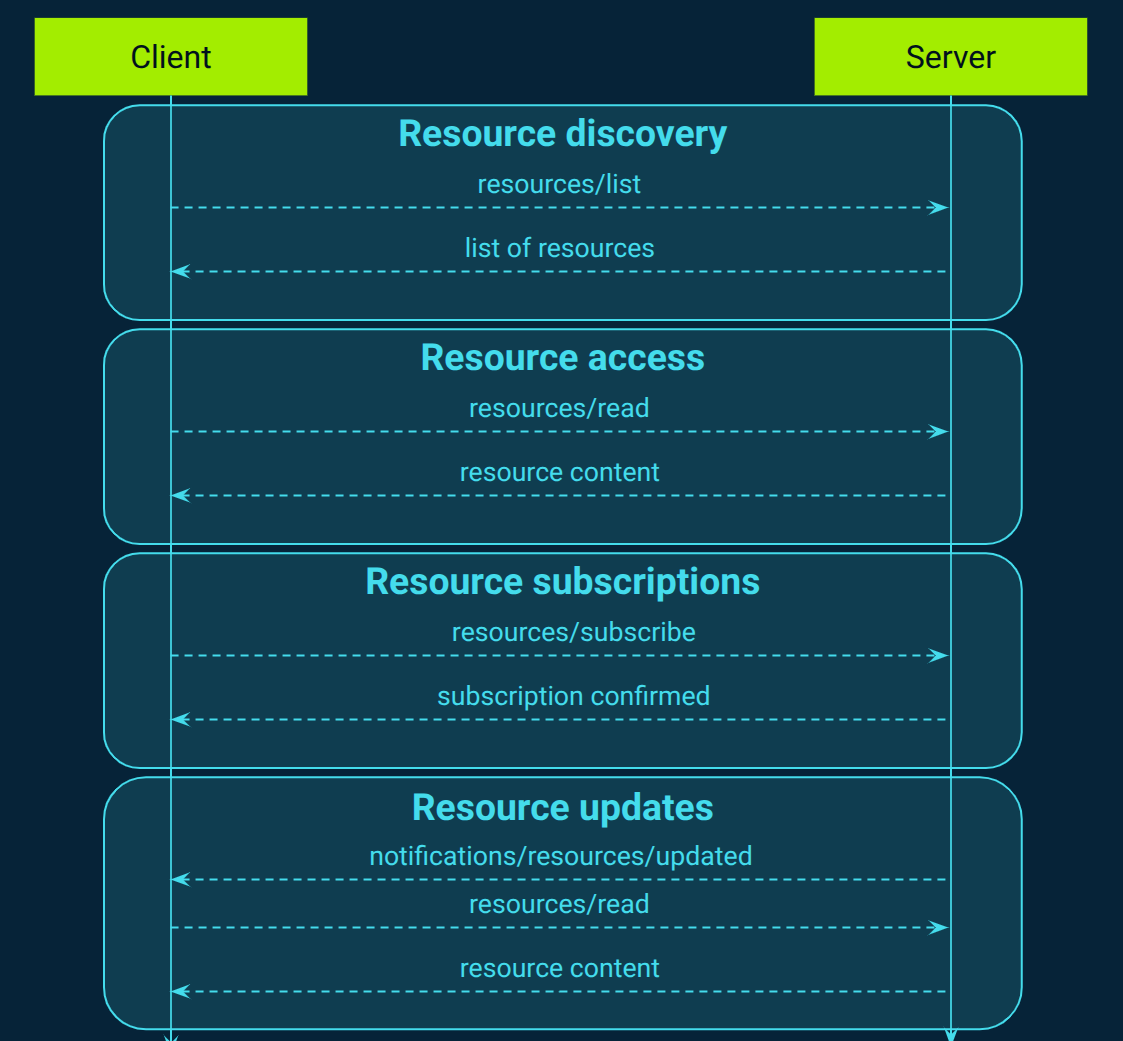

Resources: Providing read-only context data

MCP offers a standardized method for servers to expose resources to clients (Figure 4), enabling the sharing of contextual data with language models. These resources encompass files, database schemas, and application-specific information, each identified by a unique URI. They serve as read-only context providers, allowing clients to access and utilize relevant data without executing actions on the server side.

To enhance flexibility, MCP supports resource templating, enabling servers to define dynamic content structures that clients can instantiate with specific parameters. Additionally, resources can be annotated with metadata such as audience, priority, and last modified, guiding clients in selecting and presenting relevant information. For instance, annotations can indicate whether a resource is intended for the user or the assistant, its importance level, and its recency, aiding in prioritization and display decisions.

Furthermore, MCP facilitates subscriptions, allowing clients to receive notifications when exposed resources change. This mechanism ensures that clients are promptly informed of updates, enabling them to maintain up-to-date context without the need for manual polling. By subscribing to resource changes, clients can dynamically adjust to evolving data, enhancing the responsiveness and relevance of AI interactions.

Prompts: Exposing reusable templates

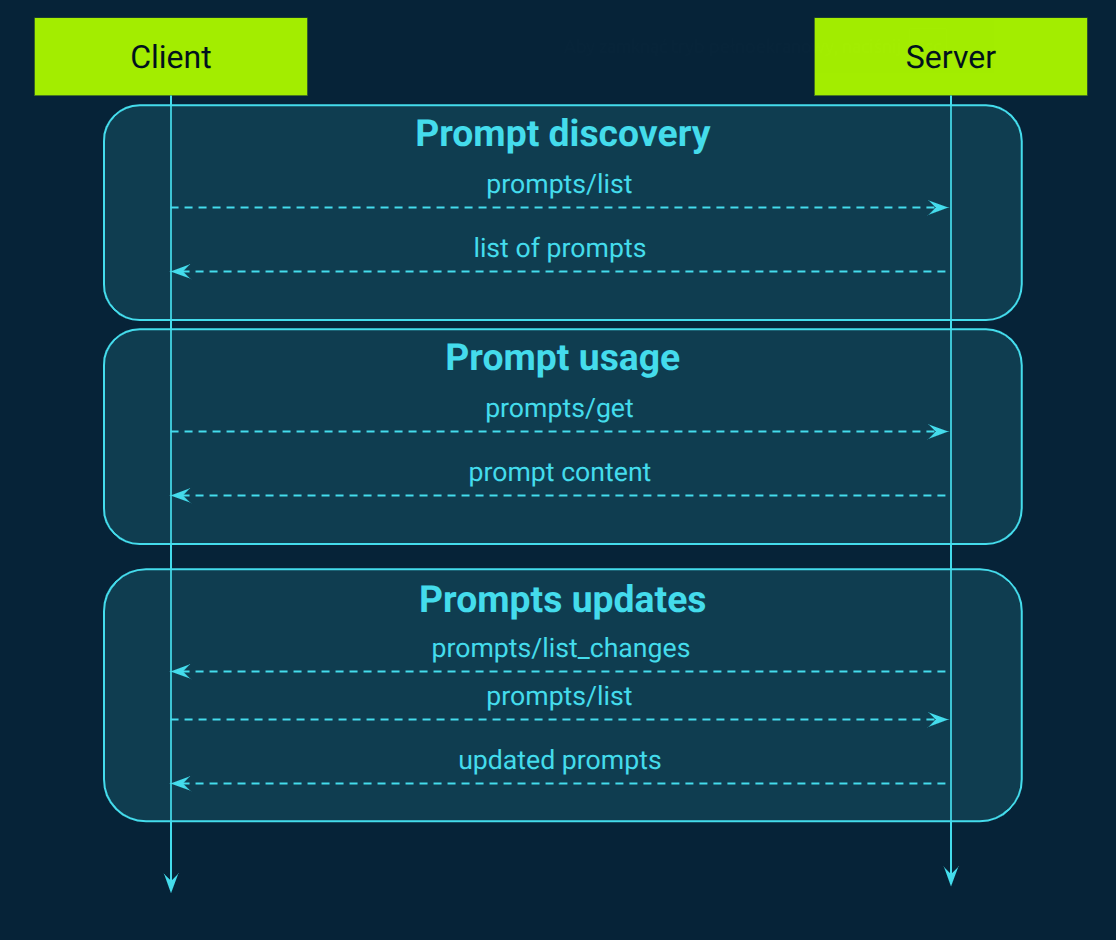

MCP provides a standardized framework for servers to expose prompt templates (Figure 5), enabling structured interactions with language models. These prompts allow servers to deliver predefined messages and instructions, guiding the model's responses. Clients can discover available prompts, retrieve their contents, and provide arguments to customize them, facilitating dynamic and context-aware interactions.

Servers can notify clients about changes to prompt templates, such as additions, updates, or deletions. When a prompt is added, modified, or removed, the server emits this notification, prompting the client to re-fetch the list of available prompts to stay up-to-date.

Also, MCP enables servers to expose resources within prompts, such as files, database schemas, or application-specific data, to clients. These resources can be seamlessly integrated into responses generated by prompt templates, eliminating the need for client-side embedding. For instance, when a prompt is designed to generate a summary of a document, the document's content can be included as an embedded resource within the prompt, all without requiring the client to manually incorporate the document's content.

Tools: Enabling AI actions and integrations

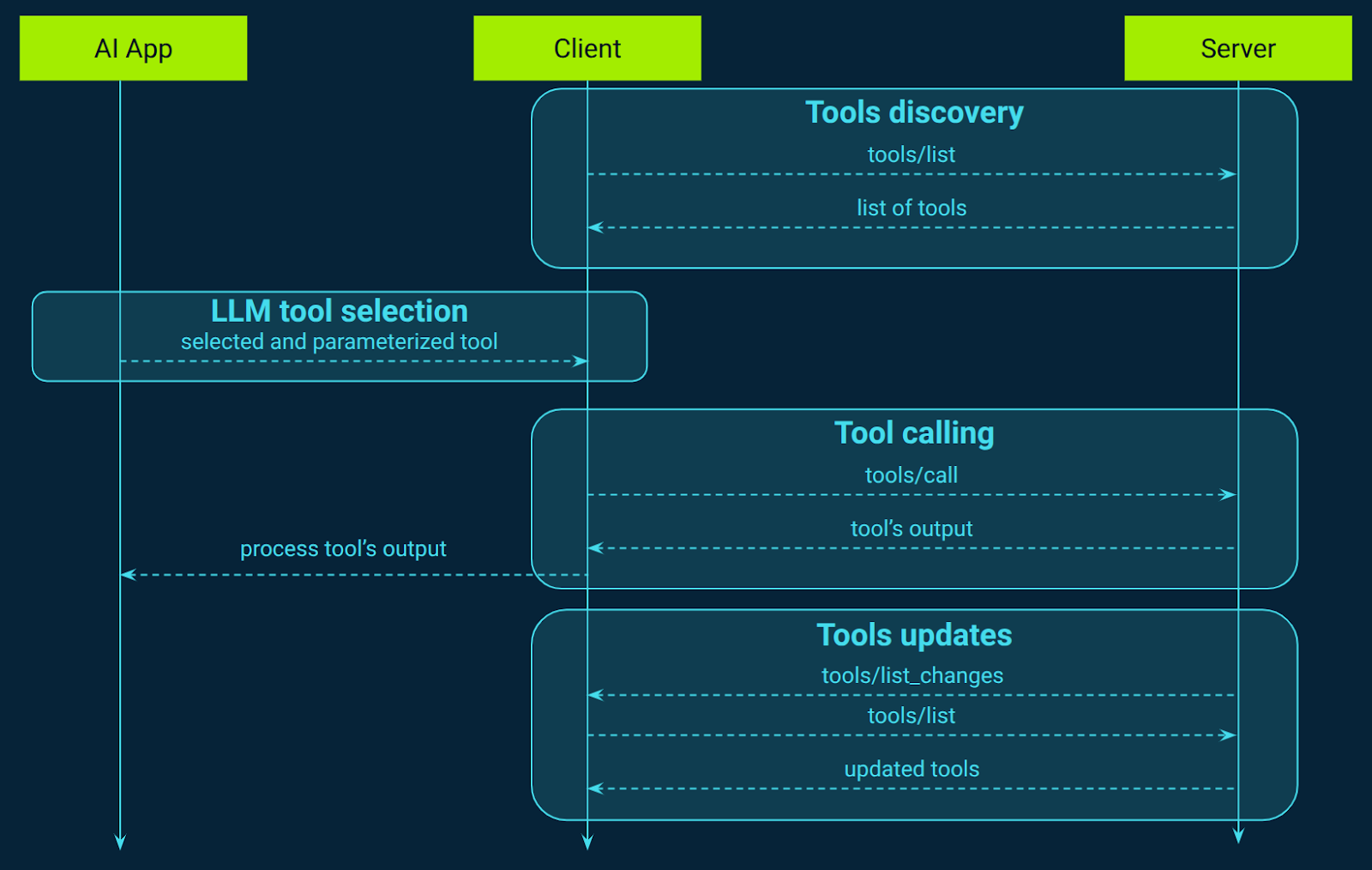

MCP enables servers to expose tools, referred to as "AI Actions," that language models can invoke to interact with external systems (Figure 6). It offers a standardized and secure method for language models to perform actions through server-implemented functions. These tools allow models to perform operations such as querying databases, calling APIs, or executing computations, thereby extending their capabilities beyond static responses. Each tool is uniquely identified by a name and includes metadata that describes its schema, ensuring structured and predictable interactions.

Tools in MCP are defined using JSON Schema, specifying the expected input parameters and, optionally, the output structure. This schema validation ensures that both the server and the client have a clear understanding of the data formats, promoting consistency and reducing errors. For instance, a tool designed to retrieve weather data might define an input schema requiring a location parameter and an output schema detailing the temperature and conditions.

Importantly, the execution of these tools is controlled by AI applications. Before invoking a tool, the model can present the user with the tool's name, description, parameters it intends to use, and ask for confirmation. This transparency allows users to review and consent to the action, maintaining control over the operations performed on their behalf.

Similarly as for prompts and resources, MCP includes a mechanism that allows servers to notify clients when the list of available tools changes. This is achieved through the special message, which servers can emit when tools are added, removed, or updated. Clients can subscribe to this notification to stay informed about changes in the toolset. Upon receiving this notification, clients are expected to send a tools/list request to retrieve the updated list of tools. This ensures that clients have the most current information about the tools available for interaction.

Additionally, tools can return resource links or embedded resources as part of their output. These resources can provide additional context or data that the model can use in subsequent interactions. Resource links are URIs pointing to external data, while embedded resources include the data directly within the tool's response. Both types support annotations that describe their intended audience, priority, and other metadata, helping clients in appropriately utilizing the resources.

MCP client features: Roots, sampling, and elicitation

MCP also defines essential interaction primitives that clients expose to servers, facilitating specific server-side tasks. These primitives enable servers to request structured information, define operational boundaries, and engage in collaborative reasoning with client-side language models. They are shortly described below.

Roots: Defining filesystem boundaries

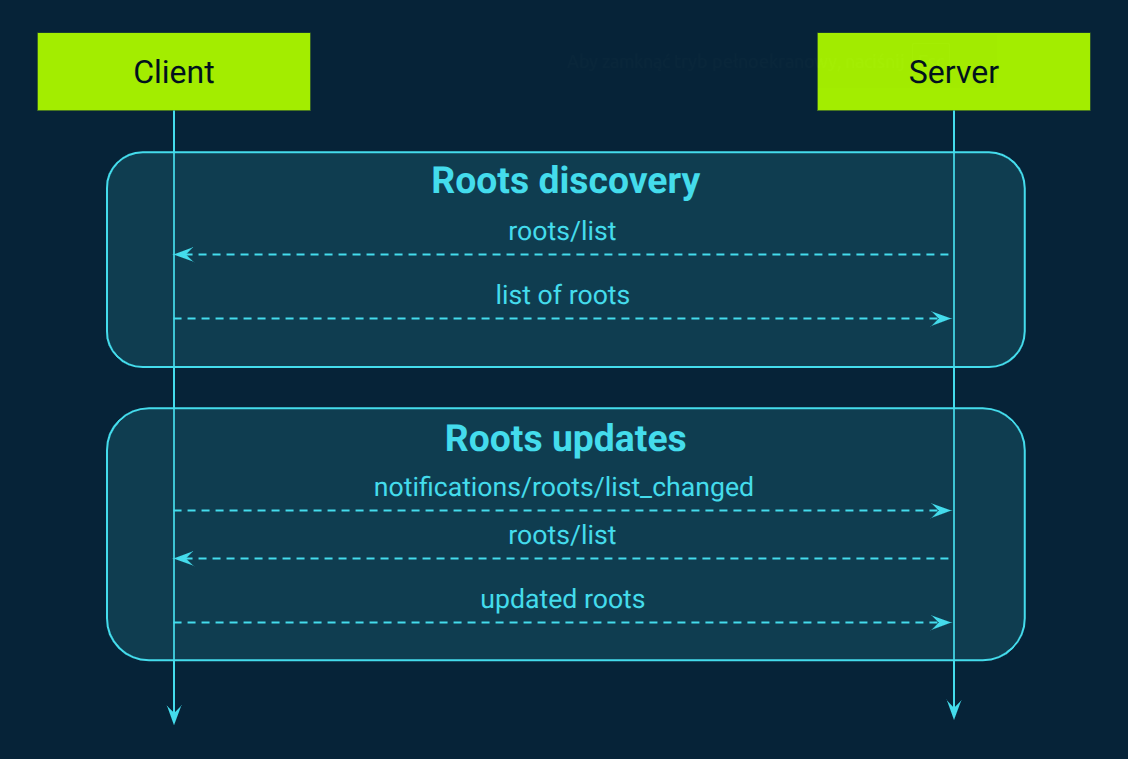

MCP enables clients to define filesystem boundaries known as "roots," which specify the directories and files a server can access (Figure 7), ensuring secure and context-aware interactions. These roots are particularly beneficial in code interpretation applications, where servers need to operate within specific project directories to perform tasks like code analysis, documentation generation, or version control operations.

For instance, an integrated development environment (IDE) acting as an MCP client can expose the current project directory as a root, allowing the server to access relevant files for tasks such as code analysis or documentation generation. This setup ensures that the server operates within the defined project scope, enhancing security and efficiency. Additionally, MCP supports dynamic updates to the list of roots, enabling clients to notify servers of changes, such as when a user opens a different project or workspace. This dynamic capability ensures that servers always have an up-to-date understanding of the client's filesystem boundaries, facilitating seamless and contextually appropriate interactions.

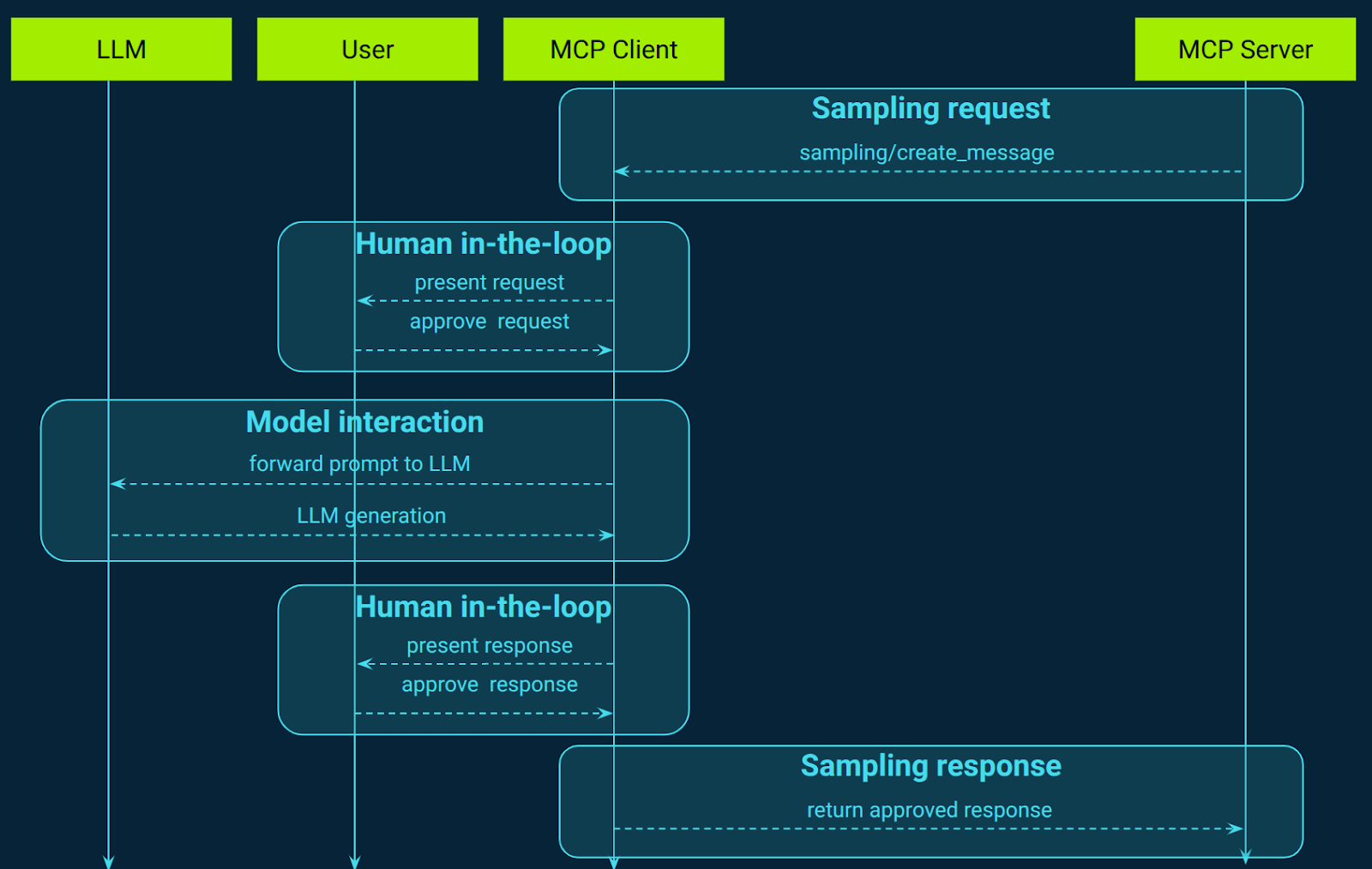

Sampling: Server-initiated LLM requests

MCP introduces an interesting standardized mechanism for servers to request language model sampling (completions or generations) via clients (Figure 8). This approach allows servers to leverage the capabilities of LLMs without directly integrating with or managing AI model access. Instead, the client, which already has access to an LLM, handles the request on behalf of the server. This setup ensures that clients maintain control over model access, selection, and permissions, eliminating the need for server-side API keys and enhancing security. Servers can request text, audio, or image-based interactions and optionally include context from MCP servers in their prompts, facilitating more dynamic and context-aware AI interactions.

Sampling in MCP enables servers to implement agentic behaviors by allowing LLM calls to occur nested within other MCP server features. This means that AI-driven tasks, such as generating summaries, analyzing data, or composing messages, can be performed as part of a larger workflow without compromising the modularity and security of the system.

The user interaction model is designed with trust and safety in mind. Before any sampling request is sent to the LLM, the client presents the prompt and context to the user, who has the ability to edit, approve, or reject the request. Similarly, after receiving the LLM's response, the client shows it to the user for final approval before sending it back to the server. This human-in-the-loop design ensures that users maintain control over what the LLM sees and generates, enhancing transparency and accountability in AI interactions.

Model selection in MCP requires careful abstraction since servers and clients may use different AI providers with distinct model offerings. A server cannot simply request a specific model by name, as the client may not have access to that exact model or may prefer to use a different provider’s equivalent model. To address this, MCP implements a preference system that combines abstract capability priorities with optional model hints. Servers can express their needs through three normalized priority values: costPriority, speedPriority, and intelligencePriority, each ranging from 0 to 1. These priorities indicate the server's preference for minimizing costs, achieving low latency, or utilizing advanced capabilities, respectively. Additionally, servers can provide model hints—strings that suggest specific models or model families. While these hints are advisory and clients make the final model selection, they guide the client in choosing a model that aligns with the server's requirements, balancing factors like cost, speed, and intelligence.

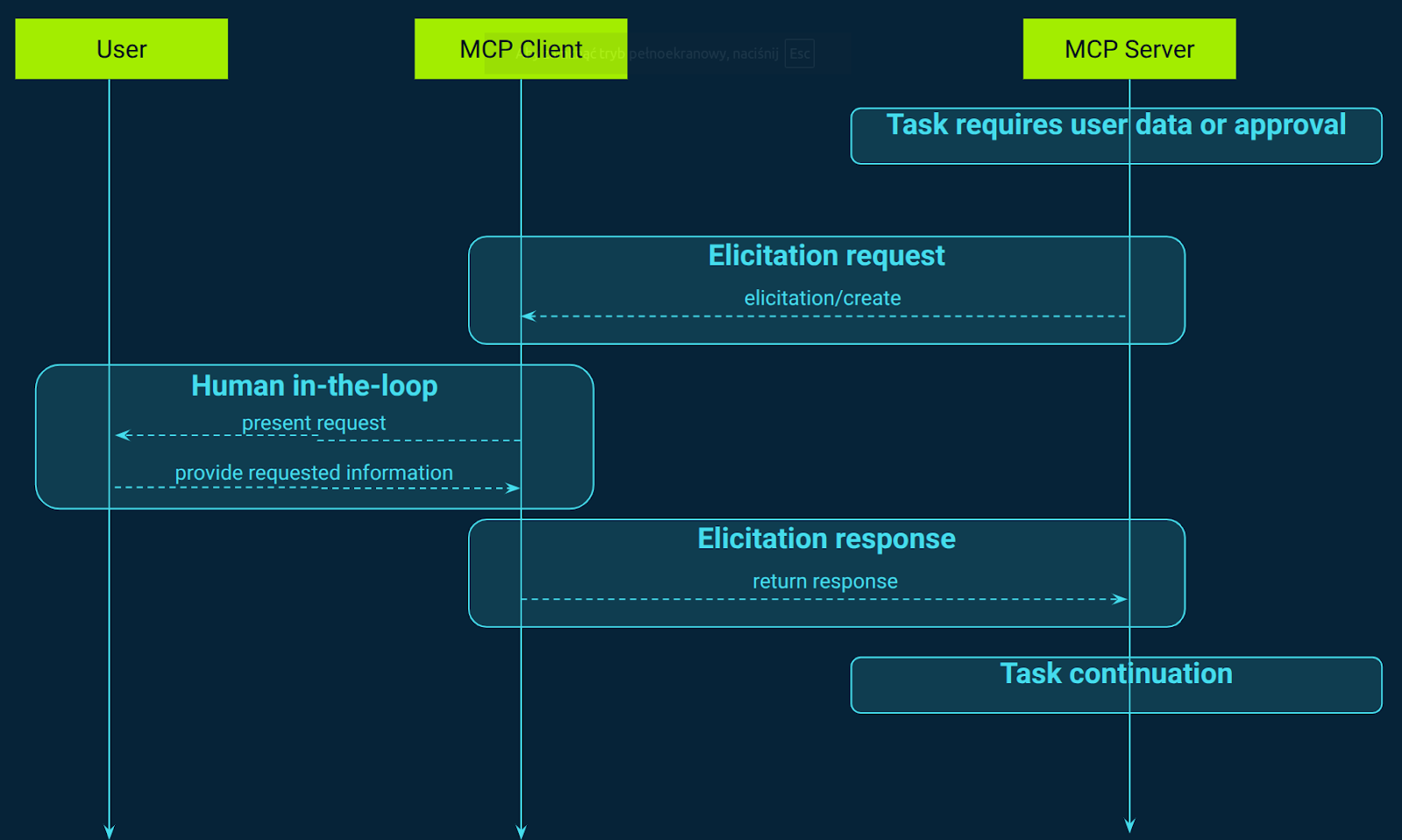

Elicitation: Interactive user input collection

MCP offers a standardized method for servers to request additional information from users during interactions, enhancing the dynamism and responsiveness of AI-driven workflows (Figure 9). This elicitation process allows servers to pause their operations and request specific inputs from users, facilitating more interactive and context-aware experiences. For instance, when a server requires clarification or additional data to proceed with a task, it can initiate an elicitation request, prompting the client to present a structured form to the user. This interaction ensures that the server operates with the most accurate and up-to-date information, improving the overall quality and relevance of its outputs.

A notable application of MCP's elicitation feature is in scenarios where user approval is critical before executing certain actions. For example, when a server intends to invoke a tool that could perform significant operations, such as modifying system settings or accessing sensitive data, it can use elicitation to request explicit user consent. The client presents the user with a clear and structured prompt, detailing the action to be taken and seeking confirmation. This human-in-the-loop approach ensures that users maintain control over potentially impactful decisions, enhancing trust and security in AI interactions.

Furthermore, MCP's elicitation mechanism supports multi-turn interactions, allowing for a conversational flow between the server and the user. This capability is particularly beneficial in complex workflows where multiple pieces of information are required over time. The server can sequentially request data, with each elicitation step building upon the previous one, creating a coherent and contextually rich dialogue. This structured approach not only improves the efficiency of data collection but also ensures that the user's inputs are accurately captured and utilized, leading to more precise and effective outcomes.

Managing session state in MCP

Maintaining a stateful session in MCP unlocks key performance, usability, and security benefits. Once the connection is established, the initial version and capability negotiation need not be repeated, so every subsequent JSON‑RPC call is compact and much faster. Persistent session handles (roots, tools, and resources) allow the server to send incremental notifications, streaming only what actually changes, which is very useful for live file trees or database updates. Because the transport channel stays open, the server can push events instantly, such as new tools or log updates, instead of forcing clients to poll repeatedly, ensuring fresher data with less load.

Additionally, server‑initiated sampling enables agentic workflows, meaning that the server can pause mid-task to ask clarifying questions or generate content via the client’s LLM. This all can be done within the same session and without external API keys or ad-hoc channels, which supports true collaboration between the server and model. Together, these features enable fluid multi-step workflows, reduce cold-start overhead, and tie every request, tool call, or sampling event to a single session ID, simplifying audit trails and permitting immediate revocation of permissions if needed.

Although an MCP connection is stateful (client and server hold a live session ID, the negotiated capability matrix, open resource handles, and change-feed subscriptions), that state is intentionally lightweight and transient. The spec notes that if the socket dies, recovery is “not catastrophic” because no durable data is lost, underscoring that the session exists only to accelerate context exchange and push notifications. Implementation guides, therefore, keep this metadata in an in-memory map or short-TTL cache, and explicitly tell developers to store anything that must outlive the socket (long-running report jobs data, multi-agent plan intermediate data) in their own database, queue, or object store. Put plainly, MCP’s session state is a transport convenience, not a workflow ledger. The protocol standardises context hand-off, but leaves ownership of enduring business logic and persistence entirely to the host application.

MCP transport layers: STDIO and HTTP

The transport layer manages all communication and authentication between clients and servers in an MCP system. It takes care of connection setup, message framing, and the creation of a secure channel for every MCP participant. By handling these low-level details, the transport layer makes sure that clients and servers can always communicate reliably, no matter what kind of environment they are running in.

MCP defines two main transport mechanisms: STDIO and Streamable HTTP. The STDIO transport uses the standard input and output streams of the operating system so that local processes on the same machine can talk to each other directly. This gives the best performance since there is no network overhead, making it the preferred option for local integration and local prototyping.

The Streamable HTTP transport uses HTTP POST and GET to send messages from client to server and can stream real time responses using Server Sent Events (SSE). This is the right choice for remote connections and supports many HTTP authentication options like bearer tokens, API keys, and custom headers. MCP recommends using OAuth for authentication tokens.

By abstracting communication details, the transport layer lets MCP always use the same JSON RPC 2.0 message format on any transport method. All JSON RPC messages must be UTF-8 encoded. MCP clients should use stdio whenever they can and use streamable HTTP for cloud-based or remote setups.

MCP authorization: OAuth 2.1 implementation

MCP embeds HTTP-level authorization using a subset of OAuth 2.1. When enabled, MCP clients act as OAuth clients requesting access tokens from an authorization server (associated with the MCP server) to access restricted MCP servers (acting as OAuth resource servers). This ensures that MCP clients can only use approved tools and resources with explicit user consent (Figure 10).

Clients start by making a protected request, expecting a 401 Unauthorized response with a WWW-Authenticate header that references the MCP server’s protected resource metadata (RFC 9728 OAuth 2.0 Protected Resource Metadata). That metadata points to one or more authorization servers, enabling the client to discover the relevant OAuth endpoints and, if supported, register dynamically (RFC 7591 OAuth 2.0 Dynamic Client Registration Protocol) using the resource parameter (RFC 8707 OAuth 2.0 Resource Indicators) to bind tokens to the correct MCP server URI.

When requesting a token, the client includes a scope parameter listing the exact permissions needed (such as tools.read, tools.execute, or resources.fs:read) based on permissions granted to the underlying host process user. The authorization server evaluates those scopes according to resource-owner permissions and issues a token limited to what’s allowed. The client then includes this token in its “Authorization: Bearer <token>” header on every MCP request, and the MCP server validates both its authenticity and that the necessary scopes are present before executing the requested actions. If permissions are insufficient or the token is invalid, the server responds with standard OAuth error codes (HTTP 403 or 401), enforcing strict least-privilege access control.

This approach provides fine-grained, context-aware access control aligned with user roles and system permissions. Every protected action is governed by scoped tokens, enabling full auditability, easy token revocation, and consistent security boundaries. If credentials are compromised or access needs to be revoked, terminating the token or the connection immediately removes the client's permissions, thus simplifying secure operations in multi-tenant or critical enterprise environments.

Only HTTP-based MCP transports need implement this authorization flow. STDIO transports should use environment-sourced credentials, and other transports should adopt their own secure best practices.

Practical examples of MCP servers and clients

MCP has moved well past “promising spec”. Hundreds of open-source and commercial MCP servers already wrap everything from code repos to SaaS apps, and mainstream IDEs and agent frameworks ship as ready-made clients

. Below are a few notable servers and some popular clients you can use today.

Popular MCP servers: GitHub, Slack, BigQuery, and more

GitHub MCP Server – GitHub’s official binary exposes dozens of repo-level tools such as list_files, create_issue, open_pr, run_workflow, and search_code. It can optionally call the host model via sampling/createMessage to draft PR descriptions or release notes.

Slack MCP Server – Announced by Slack’s platform team, this remote server maps the Slack Web API into tools like send_message, list_channels, add_reaction, search_messages, and upload_file. It streams workspace data but performs no LLM calls itself.

BigQuery MCP Toolbox – Google Cloud’s “MCP Toolbox for Databases” publishes data-warehouse tools such as execute_sql, list_dataset_ids, get_table_info, dry_run_cost, and stream_results. Query results are streamed raw, and summarisation can be done client-side, so the server itself does not use sampling.

Windows Command-Line MCP Server – A community package that surfaces Windows automation through tools like execute_command, execute_powershell, list_running_processes, get_system_info, and get_network_info. It provides controlled shell access but never asks the client to sample text.

Figma “Dev Mode” MCP Server – Figma’s beta server streams design context with tools such as get_frame_geometry, list_components, get_design_tokens, export_svg, and get_color_styles. It hands raw vectors to the agent and any code generation happens in the client.

CData SharePoint MCP Server – A commercial server that connects AI agents to SharePoint lists, libraries and permission metadata, giving enterprise chatbots secure, real-time access to intranet content.

MCP client applications: Claude Desktop, VS Code, and IDEs

Claude Desktop – Anthropic’s macOS/Windows app now includes a directory UI for installing and managing MCP servers (Google Drive, Slack, Canva, and more) with a single click, making the ecosystem accessible to non-developers.

LangChain/LangGraph MCP Adapters – The langchain-mcp-adapters library auto-converts any remote MCP tool into a LangChain Tool, so agent graphs can reason over dozens of servers with no extra glue code.

OpenAI Agents SDK (MCP extension) – OpenAI’s Python SDK includes MCPClientManager, enabling assistants to load tool catalogues from multiple servers, validate JSON schemas, and invoke them through native function-calling.

Visual Studio Code (Agent Mode) – VS Code’s AI integration lets developers register MCP servers in settings or pick from a curated marketplace, expanding chat capabilities to databases, APIs, and internal tools straight from the editor.

JetBrains IDEs – IntelliJ IDEA and sibling IDEs added an MCP-client UI where users paste a server config or choose one via slash-command, bringing the same tool catalogue into JetBrains’ AI Assistant pane.

These examples show how quickly the MCP ecosystem is standardising LLM-to-tool connectivity. Server authors wrap a platform once, and every compliant client (whether a desktop chat app, an IDE, or a Python agent framework) can leverage it immediately.

CodiLime case study: Integrating MCP with Network-chat assistant

In CodiLime, we built a network‑chat assistant powered by a ReAct‑style LangChain agent. Our goal was to let users interact with various network devices in a containerlab setup via chat. To do this, we created a set of tools for different virtual routers from specific vendors. These tools can connect to each device, authenticate, authorize, identify the vendor, and execute commands such as ping, show interfaces, show bgp summary, and so on.

As we think about packaging these tools into an MCP server, we see clear benefits. First, once wrapped and exposed over an MCP server, any developer using Claude, GPT, Gemini, or other LLM front-ends could discover and invoke our tools without writing custom integration code. That means other AI agents or apps can immediately tap into device commands without the N × M adapter headache. It’s like providing a universal interface that turns our network-specific tools into plug‑and‑play components across models.

Second, by packaging the tools into a standardized MCP server, other development teams, especially those knowledgeable in networking, can easily contribute new capabilities. They can build or extend tools for new vendors by following the same MCP contract, without worrying about the underlying LLM or custom client implementation.

Third, using MCP helps centralize authentication and authorization logic. Instead of embedding credential checks inside the LLM agent, we can manage session tokens, role‑based permissions, or user ACLs at the server layer. This means the AI app user is granted only the network‑device access he is authorized for, enhancing security and governance without additional work at the agent layer.

By transitioning our custom networking tools into an MCP server, we shift from brittle, per-model integrations to a modular, reusable framework. Other developers can leverage secure, discoverable, and interoperable tools effortlessly. This means faster development of new AI capabilities, better team collaboration, and robust control over access, all without reinventing the wheel for each LLM or device type.

Common MCP implementation patterns

MCP architecture establishes a fully bidirectional client–server model in which both sides expose standardized protocol primitives that support rich, modular integration and workflow orchestration. On the server side, MCP supports prompts, resources, and tools. Meanwhile, on the client side, MCP defines primitives including roots, sampling, and elicitation. This architecture supports multiple communication flows. Together, this flexible interplay of server- and client-facing primitives makes MCP a powerful protocol for building modular, interactive, and secure LLM‑based workflows. Below, we describe a set of common patterns that outline different combinations of these capabilities and use-case goals.

Pattern 1: Prompt library server

The first common pattern is the prompt library server, typically managed by LLM or prompt‑engineering teams. It publishes a catalog of parameterized prompt templates through MCP’s prompts-related primitives. The goal is to centralize best‑practice system prompts so that any MCP‑aware chat client can autocomplete them as slash‑commands. This kind of server is often used by frontier‑model providers shipping “golden” prompts and by enterprise prompt‑ops teams running A/B tests on prompt templates.

Pattern 2: SaaS platform wrapper

Another pattern for MCP servers is the SaaS platform wrapper, such as servers tailored to Slack, Teams, or Discord, usually provided by enterprise SaaS vendors. These wrappers expose tools like send_message, list_channels, or add_reaction, and may optionally surface resources for files shared in channels. They exist so that agent developers can seamlessly integrate such platforms’ functionality into workflows without wrestling with OAuth scopes or real‑time messaging APIs.

Pattern 3: Tool catalog server (adapter hub)

The third pattern is the tool catalog server, often dubbed an “Adapter Hub,” which is offered by AI‑agent frameworks. It proxies dozens of underlying SaaS APIs, such as Stripe, GitHub, or HubSpot, and re‑emits them as MCP tools so a manager agent can choose deterministically. This approach dramatically reduces the combinatorial explosion of connectors, and frameworks like LangChain/LangGraph then translate those remote definitions into local tools automatically.

Pattern 4: Retrieval server (RAG)

Fourth, you have the RAG (retrieval server), commonly deployed by enterprise platforms. It exports tools such as search_corpus, get_chunk, or list_similar, along with streaming document snippets for context. This architecture enables secure, firewall‑protected documents to remain inside the enterprise environment while still powering answer generation externally. Sampling may be used occasionally, for instance, to pre‑summarise a long PDF before returning a concise abstract to the client.

Pattern 5: Code repository server

The fifth type is the code repository server, typically provided by LLM vendors or developer‑tool vendors. It offers tools like create_pr, run_tests, or grep_repo, often built on sample “Git” or “filesystem” reference servers. This structure gives coding assistants structured access to diffs and CI logs, avoiding brittle HTML scraping. Sampling is frequently used here, as the server can send a createMessage sampling request to ask the host LLM for an inline code review or a commit message, and then apply the answer automatically.

Pattern 6: LLM-powered tools server

Sixth is the LLM-powered tools server, sometimes referred to as internal‑model microservices, often used by enterprises with proprietary LLMs. These services offer domain‑specific tools, such as classify_risk(text) or generate_contract_clause, where the server calls its private model internally, so the host never sees the model key. This architecture encloses IP‑sensitive or regulator‑approved models, while still allowing any agent to call them via MCP. Sampling is handled entirely inside the server, as the host only sees a regular tool result without needing the internal model credentials.

Pattern 7: Clarification and review server

Seventh is the clarification and review server, used by many AI‑agent providers, which focuses on pure sampling. It typically exports minimal stub tools and relies on the sampling capability to pause a workflow and ask follow‑up questions or gather summaries (for example, “Is this the right customer?” or “Write a TL;DR for legal”). Its main purpose is to insert UX‑critical or safety‑critical queries into workflows in a controlled manner. Sampling is the core feature here, as the server sends a createMessage sampling request, the client forwards it to the host model, and the completion is returned seamlessly, without exposing API keys.

Pattern 8: Interactive prompting server

The final pattern covered in this article is the interactive prompting server, which leverages MCP’s elicitation feature to dynamically request structured input from users. This pattern supports interactive workflows by enabling the server to pause execution and ask follow‑up questions, such as clarifying missing parameters or confirming intent, before proceeding. The server issues an elicitation/create request with a JSON schema that defines exactly what data it needs, and the client renders a form or prompt for the user to complete. Once the user responds or declines, the workflow continues or aborts accordingly, allowing for multi‑stage conversational logic driven by human-in-the-loop input.

Overall, these mentioned patterns illustrate how an MCP server can range from a simple prompt library to a sophisticated interactive microservice with nested LLM sampling and elicitation. Sampling remains optional but highly effective when the server needs short bursts of model intelligence without holding its own credentials. Elicitation adds structured, user‑driven interaction capability, which is ideal for clarification, safety checks, and guided workflows. Regardless of your role, be it an LLM lab, agent framework, SaaS vendor, or enterprise, you can expose capabilities via MCP once, and any compliant agent can integrate them immediately.

MCP security considerations: Threats and mitigations

MCP’s ability to deliver highly flexible AI-agent workflows and deep tool integration also significantly broadens the attack surface. As organizations adopt MCP for orchestration between LLMs and external systems, they expose new vectors. Below, we provide an overview of the most critical threats introduced by MCP.

First is the confused deputy problem, a scenario where an MCP proxy server uses a static OAuth client ID to interface with third-party APIs. Malicious actors can exploit stale consent cookies or dynamic client registration flows to hijack authorization and receive tokens intended for legitimate users. This enables attackers to steal authorization codes and impersonate users within downstream services, bypassing vital permission boundaries.

Second, the token passthrough anti‑pattern occurs when MCP servers accept tokens issued to other services without validating audience claims, then forward them to resource providers. This opens up attacks where clients bypass audit logs, rate‑limiting, and security policies enforced by the MCP layer. To mitigate this, servers must explicitly verify that tokens were issued for their canonical identifier and refuse any that are not.

Third, session hijacking and prompt injection pose significant risks in long‑lived or resumeable transports such as SSE or HTTP streams. Attackers who obtain or guess session IDs may inject malicious events or impersonate existing sessions that could make LLMs execute harmful actions. Preventatives include using secure, non‑deterministic session IDs, binding them to user-specific identity, and rejecting session IDs that lack proper authorization context.

Fourth is the threat of prompt injection, where adversarial content, masked as benign messages or payloads, coerces LLMs into executing unintended or malicious tasks via MCP. Attackers can embed hidden instructions in user inputs or connector metadata, exploiting the agent’s trust in server prompts. Strong input filtering, vetted tool definitions, and adversarial testing are vital to mitigate this subtle but dangerous vector.

Finally, tool poisoning and supply‑chain manipulation represent emergent attack vectors. Researchers have demonstrated how malicious MCP servers can manipulate LLM preference, tool metadata, and tool chaining to coax sensitive data exfiltration without detection. Mitigations include cryptographically signed tool definitions, immutable versioning, and policy‑based access control that enforces fine‑grained use of tool capabilities.

Collectively, these risk categories underscore the necessity of adopting deep security hygiene throughout the MCP ecosystem. Notably, the MCP standard itself has been adapted to account for emerging threats, incorporating precise safeguards and recommended practices into its evolution, ensuring both functionality and security in tandem.

Summary: The key takeaways on the Model Context Protocol

In this blog, we introduced the Model Context Protocol, outlining what it is, why it was created, and how it standardizes communication between MCP clients and servers, ultimately streamlining the development of AI applications and agents. We highlighted the pressing need for MCP across different actors in the AI ecosystem, showing how it addresses key integration challenges and enables more seamless, modular, and interoperable workflows.

We also explained the security measures embedded within MCP, designed to ensure safe and controlled interactions between AI applications, clients, and servers. A set of practical patterns for building MCP servers was presented, each targeting specific goals or use cases. At the same time, we reviewed the potential security risks that can arise from improper implementation of MCP. While MCP doesn’t solve every problem in AI integration, it does bring much-needed order, clear role separation, and structured functionality. As the protocol evolves, we can expect new features and standards to be added in response to emerging challenges and community needs.